Why it is great diving with sharks in winter

Cage diving in winter!? Why it’s great to dive with sharks in winter People are often put-off by the fact that ‘you are getting wet, in the ocean, in WINTER’. But in actual fact, diving with sharks in winter is not the worst experience ever 😉 The water along the West coast can be clearer and warmer in winter due to several factors: 1. Ocean Currents: The West coast of many continents, including North America, is influenced by warm ocean currents such as the California Current. These currents bring warmer water from the south, resulting in relatively higher water temperatures along the coast. 2. Offshore Winds: During winter, the West coast often experiences offshore winds that blow from the land towards the ocean. These winds push the surface water away from the coast, allowing deeper, clearer, and warmer water to rise to the surface. 3. Rainfall and Runoff: Winter is typically the rainy season in many regions along the West coast. Heavy rainfall can wash away sediments, pollutants, and other impurities from the land, resulting in clearer water along the coast. 4. Upwelling: While upwelling is more common during the summer along the West coast, it can still occur in winter. Upwelling is a process where cold, nutrient-rich water from the deep ocean rises to the surface. This water is often clearer and can contribute to the overall clarity of the coastal waters. It’s important to note that these factors can vary depending on the specific location along the West coast and the prevailing weather patterns.

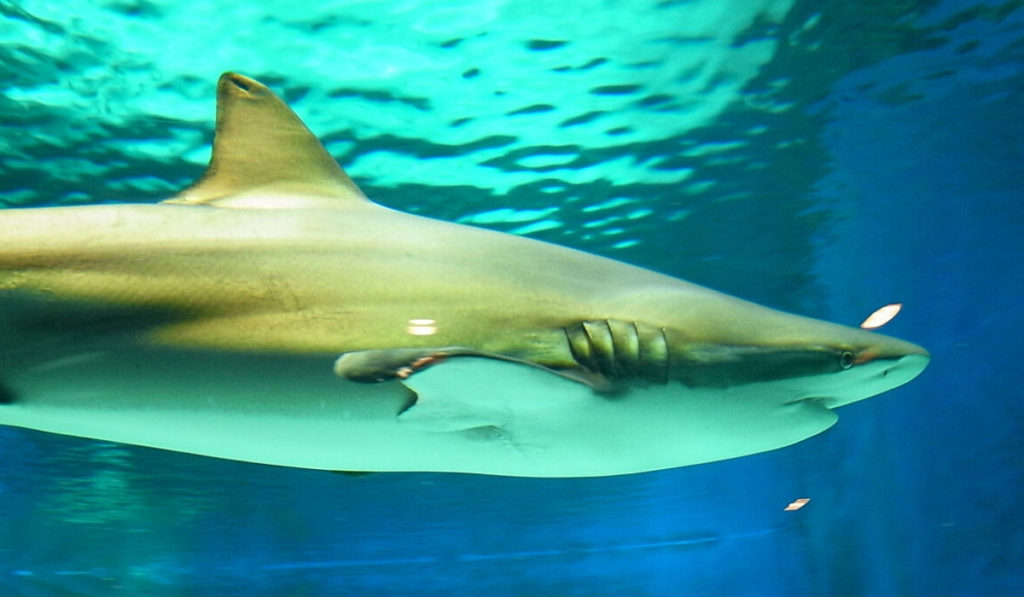

Bronze Whaler Sharks

Bronze Whaler Sharks Some interesting things that make these ‘bronzies’ unique… This shark gets its name from its bronzy-grey to olive-green coloring. It is the only species of requiem shark in the genus Carcharhinus that lives in temperate rather than tropical waters. They occur throughout the world but the distribution is patchy, with what appear to be regionally isolated populations that have little exchange between them (Compagno et al. 2005). Order – Carcharhiniformes Family – Carcharhinidae Genus – Carcharhinus Species – brachyurus Common Names English language common names for this species include narrowtooth shark, bronze whaler, cocktail shark, cocktail whaler, and copper shark. Other common names include: bronzie (Afrikaans)koperhaai (Afrikaans, Dutch)squalo ramato (Italian)kuroherimejiro (Japanese)cacão (Portuguese)tubarão-cobre (Portuguese)tiburón cobrizo (Spanish)tollo mantequero (Spanish)karcharinos vrachyouros (Greek) Danger to Humans According to the International Shark Attack File, the bronze whaler shark has been implicated in fifteen attacks since 1962, one of which resulted in a fatality. It is considered potentially dangerous to humans (ISAF 2018). Conservation IUCN Red List Status: Near Threatened The bronze whaler was listed as “Near Threatened” on the IUCN Red List in 2003. This assessment is based on the fact that it does not appear especially abundant anywhere. Instead, it appears sparsely distributed across small regional isolated populations around the world. The bronze whaler is locally common in some parts of its range; There have been population declines in New Zealand that have been attributed to overfishing (Duffy and Gordon 2003). > Check the status of the bronze whaler shark at the IUCN website. The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species. Geographical Distribution The bronze whaler shark has a worldwide distribution in warm temperate and subtropical waters in the Indo-Pacific, Atlantic, and Mediterranean (Compagno et al. 2005). Habitat The bronze whaler shark commonly occupies a variety of habitats from shallow bays and estuaries to inshore and continental shelf areas. It has been found from the surf line to depths of up to 328 feet (100 m), but is believed to range deeper (Duffy and Gordon 2003). Biology Distinctive FeaturesThe bronze whaler shark is a large classically shaped requiem with a pointed snout. It has characteristic narrowly triangular hook-shaped teeth. The upper teeth are sexually dimorphic, the males having proportionately longer and more hook shaped teeth than the females and juveniles. The eyes of this shark are circular and relatively large. Bronze whaler sharks have moderately large pectoral fins with narrowly rounded or pointed tips. The caudal fin has a bulge near the base of the front edge. This species lacks an interdorsal ridge (Compagno et al. 2005). The shark is sometimes confused with dusky shark (Carcharhinus obscurus), blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus), sandbar shark (Carcharhinus plumbeus), and spinner shark (Carcharhinus brevipinna), it can be distinguished by its distinctive upper teeth as well as the lack of any pronounced body markings and lack of an inter-dorsal ridge (Compagno et al. 2005, Duffy and Gordon 2003). ColorationThe bronze whaler shark is bronzy grey to olive-grey in color on its dorsal surface and white on the ventral surface. This counter shading serves to camouflage the animal from predators or prey below. This species has dark markings on the edge of its fins and white or dusky tips. Bronze whaler sharks are often confused with blacktip sharks or spinner sharks because of their markings (Compagno et al. 2005). DentitionJuvenile bronze whaler sharks have teeth in the upper jaw that are finely serrated and have erect symmetrical cusps. Adult bronze whaler sharks on the other hand, have narrowly triangular finely serrated cusps in the center of the upper jaw, which become more oblique as they move out towards the corners of the mouth. The lower teeth are characterized by more oblique cusps and are finely serrated as well. Tooth counts range from 14 to 16 on either side of the upper jaw and 14 – 15 on either side if the lower jaw. Upper jaw teeth are sexually dimorphic in adults – see above Size, Age, and GrowthBronze whaler sharks grow to maximum size of around 295 cm, but may attain lengths of 350 cms in rare cases . Size at maturity for males is 206-235 cm and 227-244 cm for females. The age at maturity is estimated at 13-19 years for males and about 20 years for females. Bronze whaler sharks are about 60 cm in length at birth (Duffy and Gordon 2003). Food HabitsThe diet of the bronze whaler shark consists of a variety of cephalopods including squid and octopus as well as sardines, mullet, and flatfish. During the winter months, large numbers of bronze whaler sharks follow the sardine shoals as they move along the coast of southern Natal in the “sardine run”. Adult bronze whalers are known to feed on other elasmobranchs such as stingrays and other sharks (Compagno et al. 2005, Duffy and Gordon 2003). ReproductionThe bronze whaler is a placental vivipararous species, which means that its embryos are nourished via a placental connection to the mother and are born alive. Gestation is estimated to last 12 months and reproduction occurs biennially. According to the limited data available, pups are born from June to January and litters contain between 7 to 24 pups with an average of 15 and are approximately 60 cms TL at birth. The bronze whaler uses inshore bays as nursery areas (Duffy and Gordon 2003). PredatorsLarger sharks may prey on juvenile bronze whales ParasitesOtodistomum veliporum is a type of fluke that has been found in the stomach and spiral valve of bronze whaler sharks in Brazil. Cathetocephalus australis is a tapeworm that can also be found in bronze whaler sharks from the southwestern Atlantic Ocean (Schmidt and Beveridge 1990). Taxonomy Günther first described Carcharhinus brachyurus in 1870. Synonyms include Carcharias lamiella Jordan and Gilbert 1882, Eulamia ahenea Stead 1938, Carcharhinus improvisus Smith 1952, Carcharhinus rochensis Abella 1972, Carcharhinus remotoides Deng, Xiong and Zhan 1981, and Carcharhinus acarenatus Morenos and Hoyos 1983. The genus name Carcharhinus is

Shark Tourism and Cage Diving

Shark Tourism & Cage Diving Myths regarding cage diving… Shark cage diving involves a large steel cage being lowered into the water, either next to the boat or on a tether, for individuals wishing to experience and learn about Great Whites up close. These individuals brave the cold water and often-poor visibility for the opportunity to get close to one of the most awesome and majestic predators. They are presented with a rare opportunity to learn and to dispel myths, about these creatures. The experience often challenges preconceived notions about Great Whites being simply mindless monsters. There is no other method to safely view Great Whites underwater. Great Whites cannot be kept in captivity successfully. Without Great White tourism and shark tour operators, Great Whites would continue to be surrounded in myth and irrational fear, with movies like “Jaws” being our main point of reference. I personally believe that cage diving is helping to save Great White Sharks by debunking many of the misunderstandings that surrounds this shark. Without Shark Cage Diving, few people would be able to witness this magnificent apex predator in its natural environment. I have been on many shark cage diving excursions, and the majority of participants express absolute awe of the creature. Those fortunate enough to witness a breach are overwhelmed by their experience. Personal interactions and experience, together with a high level of understanding and knowledge imparted by the ship’s crew, allow individuals to better understand the role and importance of apex predators in our oceans, and many go away with a changed mindset. Cage diving is currently practised off the coasts of South Africa, Australia and Mexico’s Guadalupe Island. Shark operators commonly chum the water with shredded fish and oils to draw in sharks for tourists and scientists to view and study. A fish head attached to a rope is also used as bait; the head is pulled away to keep the shark interested in the boat. In South Africa, this practice is limited to the Gansbaai and Mossel Bay Areas. Operators in False Bay are more strictly controlled and are not allowed to use chum, so they use tuna heads and seal decoys as bait to attract sharks to the boat. The practice of cage diving has raised fears that sharks may become more accustomed to the presence of people in their aquatic environment, and that they may begin to associate human activity with food, perhaps leading to an increase in the number of attacks on humans. Cage-diving detractors also maintain that the reason for attacks is that the sharks become conditioned to associate humans with food. Their reasoning, however flawed, is based on the idea that when a shark finds a human in the water, it will be expecting food, and this will cause it to attack the swimmer or surfer. “it is a myth that shark attacks and shark cage diving is connected” South Africa is at the forefront of this debate because of the tremendous growth of cage diving in the Western Cape over the last 15 years. The Worldwide Fund of Nature (WWF), formerly known as the World Wildlife Federation, has conducted extensive research on this issue and reports that there is no scientific link between cage diving and shark attacks. The Shark Trust, based in the United Kingdom, concludes the same from their research, stating that not enough evidence is available, especially because most attacks take place away from cage-diving locations. The City of Cape Town, which has also conducted its own research since 1998, concurs that linking shark attacks to cage-diving practices is purely hypothetical. An exhaustive study conducted by doctoral student, Alison Kok, as part of the Save Our Seas Foundation’s White Shark Project, shed valuable light on the subject. Kok investigated the impact of chumming on White Sharks, to see whether the sharks were being conditioned by the cage-diving boats. Her research suggested that the ecotourism activity like cage diving has a limited impact on the behaviour of White sharks. Tagged animals in the experiment displayed a near ubiquitous trend in decreasing response to the chumming boat with time, contrary to what was expected. Even sharks that frequently acquired food rewards stopped responding to the boat after several interactions. No positive conditioning to the boat was observed in the study. It also demonstrated that White sharks are not simple-minded eating machines and frequently ignored chumming and baiting activities.